There’s been renewed discussion about real wages and the associated measurement issues. The main issue concerning these data in 2020 and 2021 is caused by compositional shifts in the work force. Lower income workers were more likely to lose their jobs during the pandemic. When this happens, these workers are removed from the sample of people used to calculate the median wage, causing the median wage to increase.

There are already many very good pieces discussing real wage measurement issues. Two worth highlighting are “Real Wages” and Aggregation: A Methodological Mess from Alex Williams, and Are Real Wages Rising? from Joseph Politano. These are great primers on real wages and various measurement tools and issues.

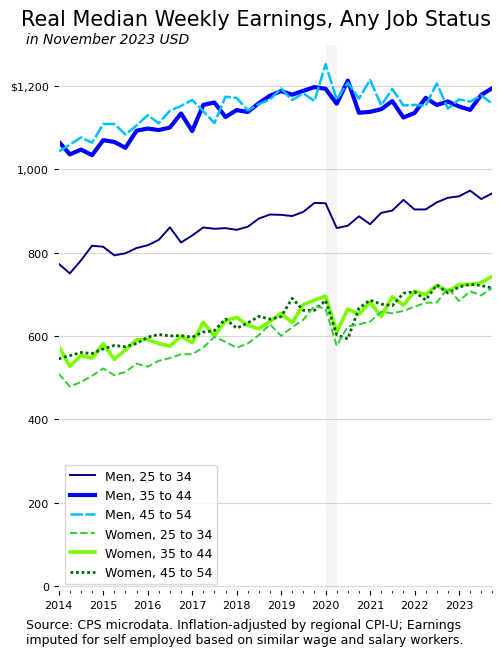

Rather than comment further on these issues, I’ve put together a chart that addresses some of these concerns, based on a very clever concept from Ryan Radia.

The basic idea is to calculate the median across everyone, whether they have a job or not. If they do not have a job, their wage is zero. This resolves the compositional issues and reduces issues that crop up from using a matched-observation wage growth measure like the Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker.

Lots of interesting results show up. There’s the gap between men and women, which is large and persistent. Men’s weekly earnings increase with age, but women’s don’t. Also, women’s weekly earnings fell during the pandemic suggesting women were working fewer hours due to care burdens. And, since the pandemic, women and younger men have seen higher rates of wage growth than older men, which is in line with findings of a compression of the US wage distribution.