By objective economic data, the US economy is doing well. The US faced a global pandemic, supply chain issues, and high interest rates, yet wages are up, consumer spending keeps growing, and unemployment is low. At the same time, consumer sentiment is currently very pessimistic and Biden is polling poorly. This gap between economic data and economic sentiment seems to be the result of a shift in how people view the economy.

Strong economic recovery

The COVID-19 recession was a massive economic shock. Large parts of the economy were shut down and unemployment climbed by nearly 12 percentage points in just 2 months. Importantly, the fiscal response was just as large. The US enacted three large scale economic relief packages, the first two under Trump and the last under Biden.

In addition to fighting the pandemic, these packages sent money directly to families, bolstered and expanded unemployment insurance and Medicaid, and gave huge amounts of money to state and local governments. The third relief package expanded eligibility for the child tax credit and increased the benefit amounts, reducing child poverty in 2021 to its lowest rate on record.

The economic relief packages are credited with the strong economic recovery, and with overcoming various headwinds that emerged during the post-COVID years. The charts below show the COVID recession recovery in real GDP per capita (left) and unemployment (right) compared with the previous five recessions.

Beyond the initial recovery, the US has so far avoided the recession that was commonly forecast for 2022. Economists generally expected higher interest rates and other economic woes to result in higher unemployment and cause a recession. As of November 2023, the consensus has shifted from “imminent recession” to “soft landing”.

Yet sentiment is bad

Despite curtailing a crisis and outperforming our international peers, economic sentiment is very bad and Biden is polling very poorly on the economy. This inconsistency has been the source of debate. The core of the debate is the shift in how people are responding to economic conditions, relative to the past. We can see this shift in the index that measures consumer sentiment.

The University of Michigan began its Survey of Consumers in the 1940s to gauge consumers’ level of optimism or pessimism. Regular monthly data from this survey have been available since 1978, and regular quarterly data are available from the mid-1960s. The index associated with this survey is closely watched and is currently near its Great Recession low, and below its low during other recessions. The current consumer sentiment around economic conditions is unmistakably very bad. It’s worth spending some time to think about why this may be the case.

Do economic indicators still explain sentiment?

In August, Twitter user @quantian1 put forth a model of consumer sentiment that fit the data very well from 1979 to 2019, and noted that it no longer fits the data, starting in 2020. They conclude that there has been a structural break in the determinants of consumer sentiment, and further suggest interest rates and housing prices as culprits.

The next chart shows predictions from a similar model of consumer sentiment based on inflation, unemployment, housing prices, wages, stock prices, and interest rates. The model explains consumer sentiment well from 1979 to 2019. The model also fits the earlier out of sample quarterly data, going back to 1965. The model does not, however, fit the data from 2020 onward.

The model incorrectly predicts record low consumer sentiment in 2020 in response to the massive increase in unemployment. If survey respondents put the same weight on unemployment in 2020 as they did in 2019, they would have been far more pessimistic, based on the model.

More importantly, the model that fits consumer sentiment before COVID suggests that consumers should be very optimistic right now. Not as optimistic as they were in the late 1990s, but just as optimistic as they were in 2019. The gap between predicted and actual values in the latest data is a useful representation of the mystery that economists have been debating.

An adjusted model

The endless “what about adjusted for inflation” or “what about housing prices” replies to already inflation-adjusted data on social media has become something of a joke among economists. The CPI includes housing, gasoline, childcare, and everything else consumers buy, and is weighted by how much people actually buy these things. Further, real wages already adjust for prices. When an economist presents real wages or adjusts data using the CPI, they have already addressed the concern that people raise over and over again. Hence the frustration.

But at an individual level, people experience all sorts of things and economists are keenly aware that the map is not the territory. For example, I am not convinced that real wages fully address the median person’s concern about prices. All people experience periods without wages, and many wage earners cannot cover the cost of starting a family or buying a first home. These are real concerns that show up in cross-sections of the data.

Additionally, people may have psychological reasons for not liking inflation even when they experience real wage growth. People may associate nominal wage gains with their own meritorious efforts while attributing price increases to unrelated external forces.

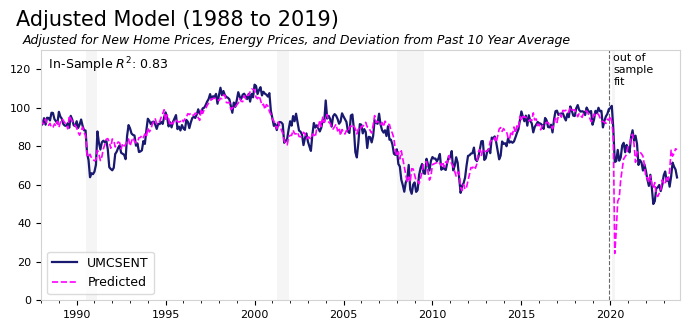

To dig into some of these questions, an adjusted version of the previous model gives in to the complaints about housing prices and energy prices, and also builds on two findings from Joel Wertheimer. The first finding is that people care about inflation and interest rates relative to what they were over the past decade. As examples, people are upset not only that mortgage rates are over seven percent, but also that mortgage rates used to be 3.5 percent. Likewise, a period of high inflation feels bad but it feels worse after a long period of low inflation. The second finding is that the model fits better when looking at the period from 1988 onward.

The next chart applies this adjusted model and finds a much better fit to the out-of-sample data from 2020 onward. Over the three months ending October 2023, the actual consumer sentiment index averaged 67. The first model predicts an index value of 95 and the second model predicts a much closer value of 78. The adjusted model also fits the actual data very well during 2021 and 2022.

The gap between the two models’ predictions for October 2023 comes from the following factors: excluding 1979 to 1987 (-4.5 percentage points), including the deviation from the previous 10-year average for unemployment, inflation, and interest rates (-8.5 percentage points), and replacing the CPI based housing index with the average new home price and adding energy prices (-4.3 percentage points).

It seems from the second model that recent pessimistic consumer sentiment is better explained if we assume that people adjust their baseline, and if we give in to the popular demand for “incorrect” CPI weights. This doesn’t preclude the possibility that people are affected by social media and that consumer sentiment reflects a misunderstanding or misrepresentation of current economic conditions. Even the adjusted model leaves around 11 percentage points unexplained. But it does present a plausible explanation for why people are responding in ways that seem inconsistent with the past.

Winning the last war

At the very least, there has been a break in what determines people’s level of optimism. The strong economy is clearly at odds with the very bad consumer sentiment. Despite outperforming our peers and achieving objectively better economic conditions than in 2019, the optimism around economic conditions seen in the University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumers is the worst since the Great Recession.

One argument is that “generals fight the last war”. The government’s response to the COVID-19 economic conditions included everything that needed to happen during the Great Recession but didn’t. The failed response to the Great Recession left major scars on the country and rippled through the world. In contrast, the economic response to COVID-19, which is sometimes called Big Fiscal or the Superdole, unequivocally achieved a superior outcome relative to past recessions. All of this is more impressive given the supply chain issues, major wars, and high interest rates. The Superdole, which ended in 2021, seems to have lined the US up for a soft landing and put us on a better growth trajectory. The Great Recession of 2008 is finally won.

Yet Biden has not been lauded for this outcome. The low unemployment, strong consumer spending, and real wage growth that mattered in 2016 is overshadowed by new concerns surrounding higher prices, higher interest rates, and unaffordable housing in previously affordable markets. Meanwhile, the promise of improved infrastructure and new factories is much closer to realization than it was in 2019, but is mostly still in planning and construction stages, while other social issues like inequality worsen. The current sentiment suggests to me that winning the last war is not enough. People want the generals to keep fighting and need to see the results.

One thought on “What’s with the Sentiment?”