The vibes debate popped back up last week. I wrote about this in September and in more depth earlier this month. Part of the recent discussion was on “real wages” and whether people are better off. This is precisely the aspect of the debate that bugs me, so I’ve come up with a chart to try to show a bigger picture view of recent economic events.

When I think about smart, good-faith people doing important research in economics, Arin Dube is at the top of the list. Professor Dube’s recent work shows inflation-adjusted wage growth among low wage workers and a compression of the US wage distribution. When sharing these findings, however, Professor Dube has received negative responses from the general public. In a sad twist of irony, it seems that the more Professor Dube is precise and accurate, the more confused and angry the responses.

There’s no reason to doubt Professor Dube’s results or methods, but it’s not clear how to interpret the negative sentiment towards his findings, or the negative sentiment reported in polls, more generally. Either this sentiment needs to be dismissed entirely or the cognitive dissonance it creates needs to be resolved in another way. To me, resolution comes from not conflating real wage growth with individuals being better off. I avoid treating the two as interchangeable because wages are only part of income and spending patterns vary massively between households. A household can experience real wage growth and still be financially worse off at year’s end.

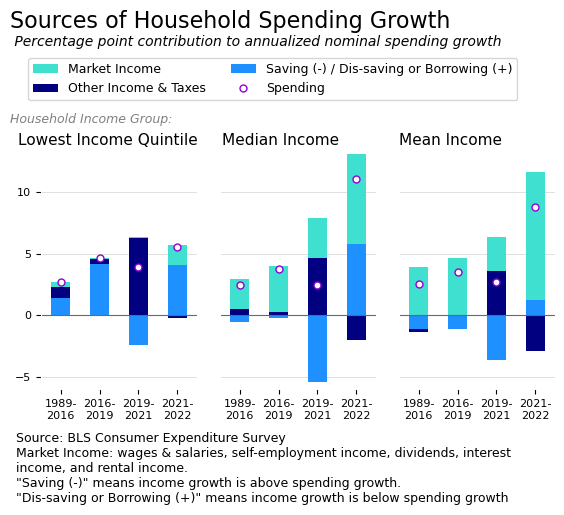

To show this point, I’ve put together a chart that summarizes the volatile economy over the past few years. Rather than isolate a key variable, such as wages, from confounding factors, such as prices, demographics, and composition effects, I’ve gone the opposite direction. I present a stylized overview and ignore the Consumer Price Index completely.

The chart shows household spending growth alongside the components that make up this growth: changes in market income, changes in all other income and taxes (on a net basis), and changes in saving. Households spend some additional amount each year, represented by the circle, and cover this spending with either new income or by borrowing or drawing down past savings. If a household’s income growth exceeds its spending growth, the leftover income becomes savings. These categories of income, spending, and saving are shown for the bottom 20 percent (quintile) of households by income (left chart), the median household (middle chart), and the average (mean) household (right chart). More background is included below.

The goal of the chart is to show the broader context for real wage growth. Specifically, I want to capture the following three missing determinants in whether someone is better off:

- Market income is not typically the source of spending growth for low income households;

- The pandemic-related boost in other income helped households across the distribution in 2021, but the disappearance of that income combined with higher spending led to significant dis-saving for the typical household in 2022; and

- The nominal spending increase for the typical family in 2022 was very large.

In other words, many people are not helped directly by real wage growth and the recent period is explicitly characterized by wages playing a smaller overall role. We can simultaneously appreciate real wage growth and realize that it doesn’t solve many problems.

To be fair, however, I should point out that much of the cumulative increase in real wages since 2019 has happened during 2023, and this is not captured in my chart, nor is the corresponding drop in inflation in 2023. My chart is admittedly a very “vibes” response to the scrupulous work of a serious researcher.

All of that said, putting real wage growth into a broader context does reveal merit in the argument that people are upset over losing non-wage income. Certainly people have been through a lot and the economy could be better; there’s no shortage of ideas for improvements. And, of course, the economy could also be a lot worse or the vibes can simply change. To some extent, it’s a question of whether consumer sentiment can remain sour longer than the economy can stay hot.

Optional Background

There are a few accounting identities in economics that are empirically true and foundational but that feel a bit funny. One of those identities represents the relationship between income y, consumption or spending c, and saving s, as follows:

y = c + s

In macroeconomics, this function (with capitalized letters) represents the idea that all income in the economy is either spent (consumed) or saved. In microeconomics, the same function represents the household budget constraint. Households receive income and face choices about what to do with it.

The reason the formulation feels off, to me, is that income is far more volatile than spending. At a national level, people and firms save more during expansions and draw down their savings during recessions. At the household level, people experience a rollercoaster of income throughout their lives, yet always consume at least some basic amount.

In fact, ideally, as individuals, we convert volatile income payments into smooth consumption patterns, across our lifespan and from week to week. Stable consumption in a world of choppy income is a basic financial goal for nearly everyone. To represent this goal, we can rearrange the function as follows:

c = y – s

The idea here is that we have some ideal level of consumption, c, and we meet it by either 1) having exactly enough income (y = c, s = 0), 2) having more than enough income and saving the balance (y > c, s > 0), or 3) not having enough income and dis-saving or borrowing the balance (y < c, s < 0).

Perhaps this is trivial, but the simple rearrangement of these variables gives interesting results when applied to the macroeconomic national accounts data or to microeconomic data on consumer expenditures. The results from the national accounts are captured in the US Chartbook section called Sources of Consumer Spending Growth. The consumer expenditures data is used in the chart above.

Data Notes

The data used in the chart above comes from the Consumer Expenditure Surveys of the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Spending, in my chart, is consumer expenditures minus spending on pensions (which is a form of saving). Market income includes wages and salaries, as well as capital income and self-employment income. Other income and taxes is the net effect of income taxes and welfare programs and other forms of non-market income.

Saving, in this context, is a negation, i.e. increased saving means a reduction in spending. When the saving / dis-saving component in the chart is positive, it means household saving was negative and the household covered spending growth through dis-saving or borrowing. When the saving / dis-saving component is negative, it means the household had money left over after covering the increase in spending.