US average hours worked were stagnant before COVID-19 but fell in the last two years for ostensibly positive reasons. The US would need large-scale labor market reform to achieve major increases in leisure time, but the current economic conditions present an opportunity to negotiate flexibility.

Background: Measuring Hours Worked

The question of “how many hours are people working?” requires a little bit of background to answer. Different measures give different results, with sometimes diverging trends.

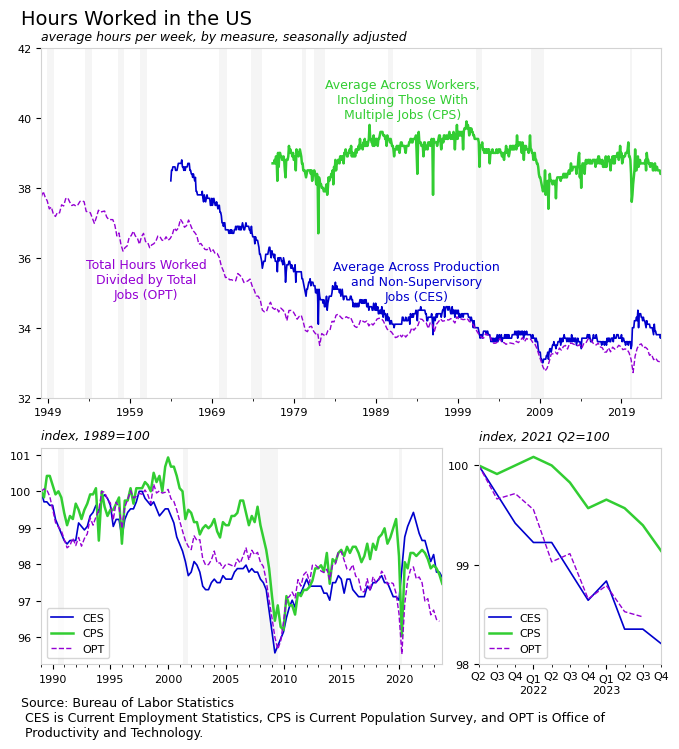

If you ask businesses about their payroll hours, you’ll get an answer that is far lower than if you ask people how many hours they work (see chart below). Researchers can explain this gap in mechanical ways. For example, a person with one 40 hour per week job and a second 10 hour per week job averages 50 hours per week in the household survey (CPS) and 25 hours per week in the payroll survey (CES). But rather than focusing on the gap between measures, let’s look at the trends in hours worked, across measures, which are isolated in the two smaller charts.

The average hours worked per job fell gradually after World War II and again during the 1960s and 1970s, but the pace has slowed considerably since the 1980s. Since 1989, hours worked have fallen between 2 and 4 percent in total, depending on the measure. Much of the pattern in hours worked, particularly since the 1980s, is cyclical; people work less during recessions and more during expansions.

One notable exception to the cyclical nature of hours worked is found in the establishment survey during the COVID-19 pandemic. The production and non-supervisory workers who maintained their jobs during the pandemic saw hours worked at these jobs increase substantially, even while other workers and the population as a whole was working less. The increase in hours worked was partially the result of a change in the composition of who is being measured.

Importantly, since mid 2021, the trends all point to a relatively sharp drop in hours worked. This decrease is particularly interesting given the current strong GDP and employment figures; the US is in an expansion so average hours would usually be rising rather than falling. In the last couple years, hours worked have fallen by one to two percent, representing as much as half of the overall change since 1989.

Hours Worked by Sector

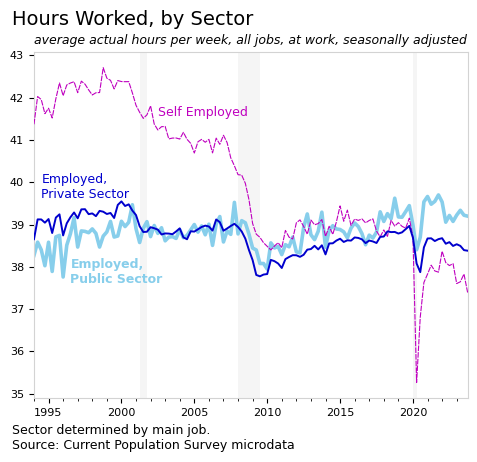

Of the measures discussed in the previous section, the household survey (CPS) shows the smallest reduction in hours worked since 2021. This should be expected, as the number of multiple jobholders increased, driving up the CPS measure and driving down the other measures. Using the CPS, let’s look at hours worked among self-employed people and among those employed in the public and private sectors (see next chart).

Trends in hours worked diverge by sector. The public sector worked fewer hours per week than the other groups, during the 1990s, but now works more than other groups. To the extent that we expect the public sector to lead the charge in reducing average workweeks, it has not been the case. Since 1994, hours worked have fallen in the private sector and risen in the public sector. The increase in hours may stem from restrictions on hiring in the sector.

Additionally, the hours reported by self-employed people have fallen from over 42 hours per week to 37 in the latest data. This group is not counted in most measures of hours worked and their work hours do not get factored into most wage or productivity measures, but they represent a sizable portion of the workforce.

The length of the workweek in the US seems relatively stuck since the 1980s. This begs the question about why we continue to work so much, even as technological advancements should allow us more leisure time. The divergence in trends by sector gives a clue about what may be going on. Self-employed workers are uniquely positioned to negotiate flexibility in work hours and to obtain leisure time, and it seems that they are doing so. In contrast, most employees in the US are tied to an inflexible system.

Why Do We Work So Much?

Economist John Maynard Keynes once envisioned a 15 hour workweek by 2030 due to rising productivity. However, with 2030 nearing, this shortened workweek is far from standard.

So why has the length of the workweek largely stalled in the US? Dean Baker and Jared Bernstein summarize the issue well in their book Getting Back to Full Employment,

The stagnation in the length of the workweek/work year has led some people to view the 40-hour workweek and skimpy vacation time as somehow natural. It is not – this just happened to be the point where we largely stopped our reduction in work hours. It makes as much sense to view the current workweek or work year as natural as it does to view a particular median hourly wage as natural

In other words, the workweek’s stagnation reflects a halt in reducing work hours rather than any natural equilibrium. So why did we stop?

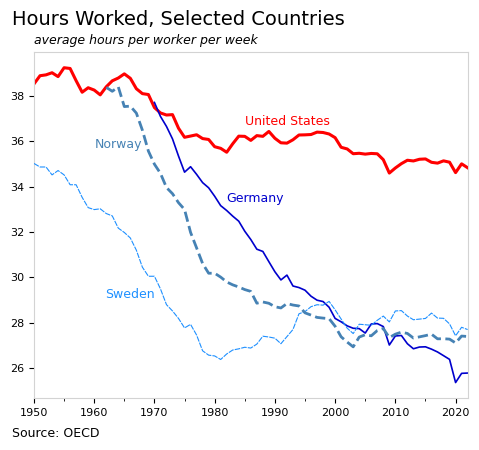

Evidence From Abroad: The Case of Sweden

International comparisons provide the most obvious evidence that the workweek has no “natural” level and is instead determined by negotiated labor market reforms. While the reduction in hours worked in the US stalled, other high income countries now work far fewer hours without sacrificing quality of life, health, or happiness.

Moreover, these changes did not just appear; other countries intentionally reduced their work hours through labor market reforms. Sweden offers an early example, followed by Norway. Germany is also a well-known case. Hours worked fell 30 percent below the US level in each of the these countries.

In the case of Sweden, the Social Democratic Party (SAP) was in government from the 1930s through the 1970s, and achieved major labor market reforms during this period. As examples, in 1938 Sweden implemented a 4-week national vacation system, and in the 1970s, Sweden lowered its retirement age, created a part-time work option for those age 60 to 65, introduced parental leave and training study leave, and added a fifth week of vacation leave. By 1980, workers in Sweden had nearly 10 additional hours of leisure time per week compared to Americans.

The Swedish model is sometimes described as “negotiated flexibility.” Rather than trying to control or dictate hours worked, the goal is to give people more options to allow them to better handle the challenges of their own lives. Workers and employers have negotiated a system that gives people more choices between work, family, studying, or leisure. As one example, the labor market in Sweden is more likely to offer a reversible part-time option so that people can study or handle temporary changes in their family without risk of losing their job. This flexibility is extremely popular among workers.

A flexible system that keeps workers and employers connected during changes in workers lives has benefits for employers, as well. When demand increases, employers can typically increase production without having to find and train new workers. So if an alternative system benefits workers and employers, why don’t we have it in the US?

Why Can’t the US Negotiate Flexibility?

In contrast to the US, the employer-worker relationship in Nordic countries and Germany is sometimes characterized as collaborative. These groups have far more opportunities to work together to solve common problems under the collective bargaining and union system that is strong in Nordic countries and Germany but weak in the US. Many businesses in the US have no system for co-determination. Likewise, workers in the US may be less likely to trust firms in cases that involve a reduction in work hours, for example.

Further, one of the strongest arguments for why the US has not achieved a reduction in work hours is that our health insurance system is tied to work. Unlike countries with national health insurance systems, US employers shoulder the fixed cost of health insurance for workers and their families. The high fixed cost associated with workers is one reason firms in the US historically prefer to reduce headcounts in response to lower demand, rather than to reduce work hours. In essence, our lack of a national health insurance system ties us to a longer workweek. The private health insurance system limits our ability to choose nonstandard work arrangements.

One of the goals behind the health insurance exchanges in the ACA was to allow people the option to buy their own health insurance and become self-employed. The exchanges allow people more options, though private health insurance can be expensive. As seen in the sector chart above, self-employed workers have reduced their work hours far more than other groups since the 2010s.

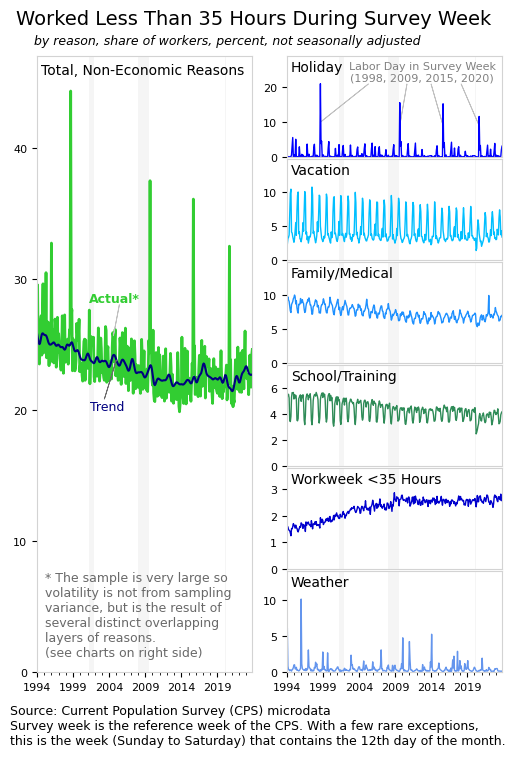

While the US faces hard limitations due to our healthcare system and collective bargaining system, we can perhaps achieve additional flexibility, along the margins. To assist in this process, it may be useful to distinguish between 1) changes in standard workweek, and 2) “non-economic” changes in the share of people who work the standard amount, for example through holidays, vacation, or other leave. Let’s see how the US is doing on both of these fronts.

Standard Workweek

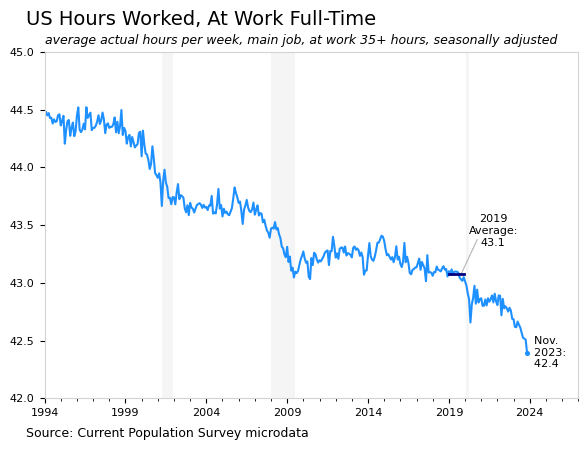

In the US, the standard workweek has been 40 hours since the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed in 1938. The typical workweek of course varies by employer, and researchers in the US generally count a workweek of 35 hours or more as “full time”. In 2023, an average of around 120 million people work full time, meaning 35 hours or more, during a given week.

Among the group of people who work full time during the CPS reference week working hours have steadily declined. This trend seems to have accelerated in recent data. In 2019, people at work full time averaged 43.1 hours of work at their main job; in the latest data, the average is 42.4 hours, a reduction of nearly two percent (see chart below).

The average hours worked in a full week are falling sharply in recent data, though it’s less clear why. A decrease of 0.7 hours per week for 120 million people is a far cry from the Swedish model, but does matter; it translates to roughly two million fewer unemployed people.

The timing of the recent decrease is perhaps more interesting than the amount of the decrease. Previous decreases coincide with weak labor markets, while the current drop coincides with a strong labor market. There has been some discussion about whether individuals are using the strong labor market to bargain for preferred policies, like telework or flexible schedules, rather than higher wages.

Non-Economic Work Absences

A trope in cartoons and TV shows a “gone fishing” sign on a storefront to represent people enjoying leisure instead of working. One of the biggest differences between American workers and workers in other wealthy nations is that American workers have much less time for fishing.

The US is sometimes called the “no vacation nation” because it stands alone among developed countries in refusing to guarantee paid vacation for its workers. At the federal level in the US, workers don’t get much more than basic legal protections for any type of leave, let alone a system of income replacement.

And while the US has 11 federal holidays per year, workers are not guaranteed time off or extra pay in the US. President Biden added Juneteenth to the list of federal holidays, which will slightly reduce hours worked, but not everyone will get to enjoy it. Many people work on holidays, and the trend in this regard is going in the wrong direction. The overall trend for “non-economic”1 work absences, and the trend for several individual categories, are shown in the following chart.

While the standard workweek seems to be falling gradually, the trend around non-economic work absences shows the opposite–fewer workers are taking time off from work. This unfortunate and surprising result suggests that a long period with a weak labor market meant lost progress on several fronts. In practice, no vacation nation has gotten worse.

Though barely visible in the chart above, there are signs that the worrisome trend started to reverse slightly in recent data. Vacations have certainly been rising over the past few years, though some of that is a rebound from the pandemic. More to this point, access to sick leave and family leave has improved. Additionally, the share of jobs with a workweek of less than 35 hours is increasing again, slightly, after a decade of stagnation. Finally, some of the trend in the above chart reflects an aging workforce that needs less time off for school or childcare.

Despite some bright spots, at an aggregate level, there has been little progress in giving people flexibility in their work schedules in the US. Indeed, the US seemed to be moving in the wrong direction on this front. More recently, a tight labor market seems to have stopped the trend of fewer people taking time off. Ultimately, it is critical to realize that these are not the types of changes that will be invented by a startup in California. Meaningful increases in the share of workers with alternatives to the full-time workweek would require large-scale negotiations that involve the government and the private sector and that result in major legislation.

Translating Productivity to Flexibility

People value leisure time and also value having flexibility in their work schedules. International comparisons show that reductions in work hours are popular and sustainable, however, structural issues in the US, such as private health insurance and low union membership, generally complicate efforts to reform labor markets. As a result, workers in the US are guaranteed no paid leave and most are tied to the standard workweek.

Current challenges aside, the US is in a relatively strong economic position for making reforms. Strong economic growth, higher productivity growth, the potential of technologies like AI, and a tight labor market all create conditions through which productivity can be translated into negotiated flexibility.

Union negotiations between businesses and workers in the auto sector and entertainment industries have been fruitful and should filter through to other industries. Part of these negotiations, as well as the negotiations in the railroad industry, involves work flexibility and paid leave. Historically, these types of labor confrontations can spur broader changes.

The post-pandemic environment also features a large increase in teleworking. While this shouldn’t affect payroll hours for employees, it does affect their actual time dedicated to work, as it reduces commute time. This is a benefit for workers and a boost in leisure time. Increased telework should equate to increased productivity as fewer inputs are required per hour of work. This effect may be reflected in the reported work hours of self-employed people, which have fallen recently, as seen in the sector chart above.

Ultimately, the US should try to achieve key labor market reforms like paid leave policies, additional holidays, mandated higher pay for holiday work, improvements in benefits systems, and breaking the relationship between work and health insurance. If not immediately possible at the federal level, progressive states can try to tackle some of these issues. Likewise, there is more room for negotiation between unions and businesses and plenty of room for more unionization.

The labor market will not be tight forever and state governments can only do so much. The federal government will play a role in any major change in leisure time in the US. There was nothing natural about the decrease in work hours in Sweden or Germany, for example; concerted national action was essential to that process. These reforms are popular and the Democratic party should try to seize the economic moment in the US.

- The term non-economic essentially means voluntary, and serves to distinguish voluntary absences like vacations or even sick days from “economic” absences like slack business conditions or being unable to find full-time work. The share of workers working part time for economic reasons is currently very low. ↩︎